A Lesson from the Past

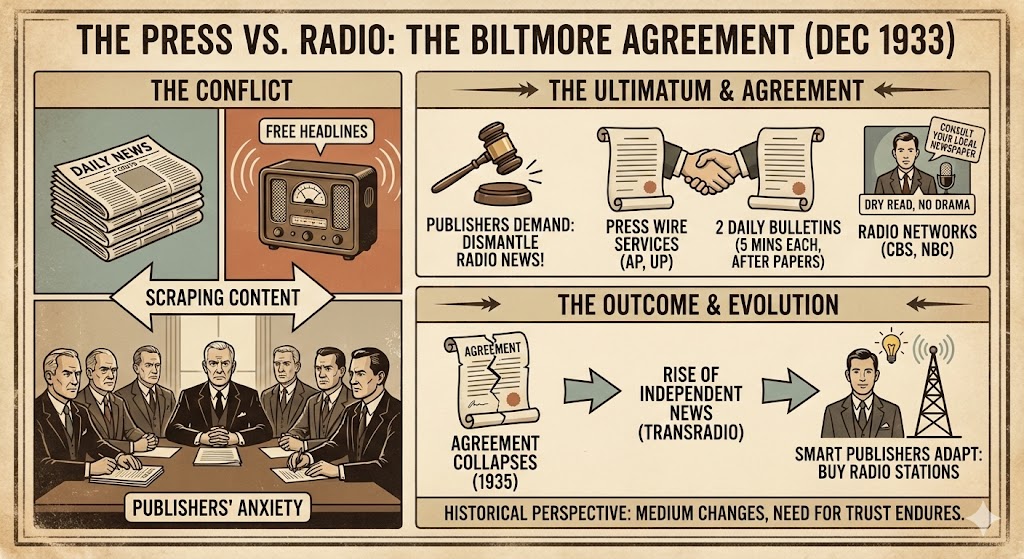

For years, publishers had viewed radio as a novelty, a parlor trick for playing jazz music and variety shows. But by the early 1930s, the novelty had bared its teeth. The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) and the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) had begun doing the unthinkable: they were reading the news.

Imagine the scene at the Hotel Biltmore in New York City on December 11, 1933. The air in the conference room was thick with cigar smoke and existential dread. Gathered around the heavy oak tables were the titans of the American press—representatives from the American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA), the Associated Press (AP), and the United Press (UP). Across from them sat the upstarts: William Paley of CBS and Merlin Aylesworth of NBC.

The tension was palpable. The publishers were furious. They had observed a terrifying phenomenon: why would a citizen pay two cents for a morning paper when they had heard the headlines for free the night before on their Philco console? The radio networks were "scraping" the content that newspapers had paid to gather, summarizing it, and broadcasting it instantly. It felt like theft. It felt like the end of the printed word.

The publishers laid down an ultimatum, which would become known as the Biltmore Agreement. It was a desperate attempt to turn back the clock. Under the terms, the radio networks agreed to dismantle their news divisions. They would cease their independent reporting. In exchange, the wire services would provide the networks with two five-minute news bulletins a day—one at 9:30 AM and one at 9:00 PM.

Crucially, these bulletins had to be broadcast after the morning and evening papers had already hit the streets. Furthermore, the radio announcers were forbidden from treating the news with any dramatic flair. They were instructed to read dryly and end every broadcast with a command: "For further details, consult your local newspaper."

The publishers left the Biltmore Hotel feeling victorious. They believed they had successfully contained the technology. They believed they had forced the genie back into the bottle, ensuring that the newspaper remained the primary source of truth for the American public.

They were wrong.

The Biltmore Agreement fell apart within months. Independent radio stations, not bound by the deal, began reading news from other sources. A scrappy new service called the Transradio Press Service emerged to fill the void, selling news directly to broadcasters. The public, hungry for speed and convenience, did not care about the publishers' profit margins. They wanted the news now, not tomorrow morning.

By 1935, the agreement was dead paper. But something fascinating happened next. The smartest publishers stopped fighting the technology and started studying it. They realized that the radio wasn't replacing the news; it was changing the delivery mechanism of authority.

Men like William Randolph Hearst and the owners of the Chicago Tribune stopped trying to litigate against the airwaves and instead began buying radio stations. They realized that their value wasn't the paper the news was printed on, but the trust and expertise of the journalists who gathered it. If the audience was moving to the airwaves, the newspaper's authority had to move there too. They shifted from being manufacturers of paper to being architects of information.

History teaches us a brutal but necessary lesson: You cannot regulate curiosity, and you cannot legislate against efficiency. The publishers who survived the 1930s were not the ones who clung to the Biltmore Agreement. They were the ones who understood that the medium changes, but the need for a trusted source endures.

The Bridge: From The Wireless to The Algorithm

Ideally, we could look back at the Biltmore Agreement as a quaint relic of a less sophisticated time. Yet, as we survey the landscape of 2026, the parallels are not just striking—they are exact.

Today, you are not fighting a wooden box with vacuum tubes. You are facing Generative AI and the fundamental shift in how Google organizes the world's information. Just as the radio announcers of 1933 summarized the day's events without requiring the listener to buy a paper, today’s AI Overviews (AIO) provide users with instant, synthesized answers at the top of the search results, often removing the need to click through to your website.

The anxiety you feel—the sense that your hard-won reporting is being "ingested" by a machine and regurgitated for free—is the same anxiety that filled the room at the Biltmore Hotel. The feeling that the tech giants are changing the rules of the game in the middle of the fourth quarter is justified.

However, the lesson of 1933 remains the only way forward. We cannot force the user to click a blue link any more than the ANPA could force a listener to ignore the radio. The "10 blue links" era of SEO, much like the "extra edition" shouted on the street corner, has passed into history.

But here is the good news, and it is significant: In a world where AI can generate infinite content, trusted human authority becomes the scarcest and most valuable resource. The AI needs you. It needs your facts, your local expertise, and your verification to prevent it from hallucinating.

The battle in 2026 is not about tricking an algorithm to rank you number one. It is about proving to the machine that you are the primary source—the "station" it must tune into. To do this, we must move beyond the old glossary of keywords and positions. We must adopt a new vocabulary for a new era.

Resolution: The Publisher's Playbook for 2026

Drawing on extensive technical analysis and the evolving standards observed in European and American markets throughout 2025, we have compiled a strategic framework. This is not merely a list of definitions; it is a map of the territory we now inhabit. These concepts represent the modern equivalent of buying the radio station—they are how you transfer your legacy authority into the digital signal.

I. The New Paradigm: Optimization for the Machine Age

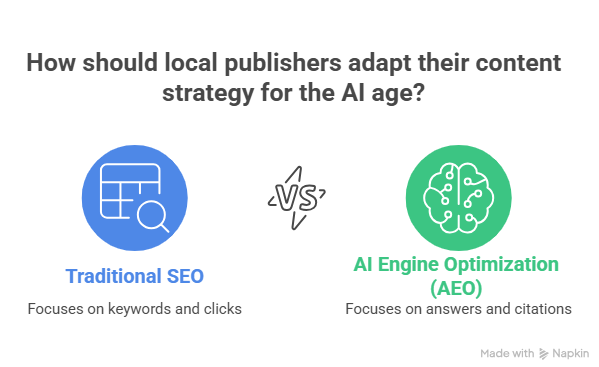

In the past, we optimized for a human scanning a list. Today, we optimize for a machine synthesizing an answer.

The Reality of AI Overviews (AIO) The most visible change in the last 18 months has been the dominance of AI Overviews. These are the comprehensive blocks of text that appear above the traditional search results. They do not just point to information; they are the information. For a local publisher, the implication is profound. The goal is no longer just the "click"—it is the "citation." When the AI constructs an answer about a local school board election or a zoning crisis, your publication must be the source it cites to validate that answer. If you are not the cited source, you are effectively invisible.

From SEO to AEO (AI Engine Optimization) This shift has given birth to AEO. While traditional SEO focused on keywords, AEO focuses on answers. It is the practice of formatting your journalism so that an AI engine recognizes it as the definitive truth. This requires a shift in editorial thinking. It means structuring articles not just as narratives, but as data-rich resources. It means clear headings, direct answers to common questions within the text, and a structure that a machine can parse easily. It is not about "dumbing down" the news; it is about making the news accessible to the world's most voracious reader: the algorithm.

The "Human-in-the-Loop" Imperative There is a misconception that AI renders human writers obsolete. The data suggests the exact opposite. Because AI models are trained on existing data, they cannot generate new facts, local gossip, or witness testimony. They cannot attend a town hall meeting. This is your competitive moat. The Human-in-the-Loop model is the gold standard for 2026 content. Use AI to organize your archives or suggest headlines, but the core content must drip with human experience. A sterile, generic report will be ignored by Google's classifiers. A report containing quotes, local nuance, and original photos serves as a signal that says: A human was here.

II. The Currency of Trust: E-E-A-T

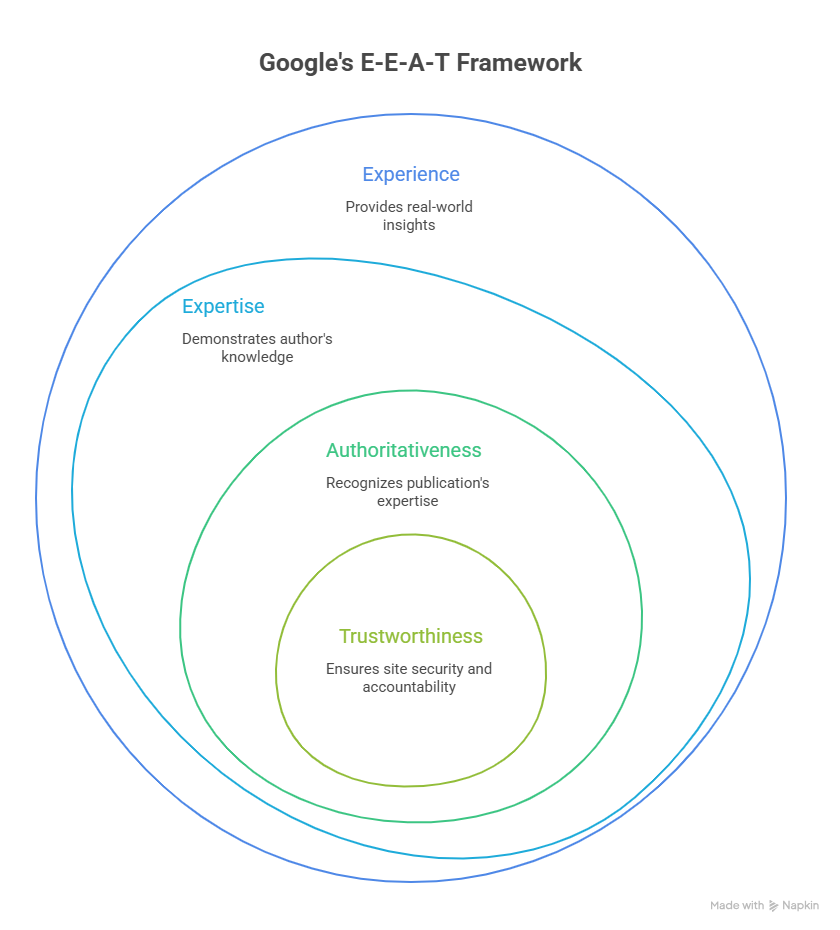

If content is the vehicle, trust is the fuel. In an ocean of synthetic text, Google’s algorithms have been retuned to aggressively filter for credibility. This is codified in the acronym E-E-A-T.

Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness While these terms have been around for a few years, "Experience" has become the dominant variable for local media.

- Experience: Did the author actually visit the new restaurant? Did they stand in the floodwaters?

- Expertise: Does the author have a track record on this beat?

- Authoritativeness: Is the publication known for this topic?

- Trustworthiness: Is the site secure, transparent, and accountable?

For a publisher, this means the byline is back. Generic "Staff" bylines are a wasted opportunity. You must build the digital profiles of your reporters. Link to their bios. Show their awards. Prove to the algorithm that John Smith is not just a string of characters, but a veteran reporter with 20 years of covering county politics.

Topical Authority: The "Beat" Reimagined In the newspaper days, you had a "beat." In 2026, this is called Topical Authority. Google no longer ranks individual pages in a vacuum; it ranks libraries of content. If you write one isolated article about a new state law, you are unlikely to rank. But if you have 50 articles covering the law's history, its local impact, and interviews with legislators, the AI recognizes you as a Topical Authority. It sees you as a comprehensive resource. The strategy, therefore, is not to chase trending keywords wildly, but to go deep—to cover a topic so thoroughly that the AI has no choice but to rely on you.

Entities and the Knowledge Graph This is the most technical but perhaps the most vital concept. Google no longer thinks in "strings" (text); it thinks in "things" (Entities). An Entity is a person, place, or concept that Google understands as a distinct object. It knows that "Lincoln" is a president, a car brand, and a city in Nebraska. Your goal is to turn your reporters and your publication into recognized Entities in Google's Knowledge Graph. This is achieved by consistent schema markup (code that tells Google "this is a person"), consistent biographical data, and citations from other trusted sources. When your reporter becomes an Entity, their work carries an inherent "trust score" across the web.

III. The Architecture of Information: On-Page Excellence

The radio publishers of the 1930s learned that even the best news failed if the signal was weak or static-filled. Today, your website's structure is that signal.

Topic Clusters To build the Topical Authority mentioned above, we use an architecture called Topic Clusters. Imagine a wheel. The hub is a "Pillar Page"—a comprehensive overview of a broad topic (e.g., "High School Football 2026"). The spokes are the detailed articles (game summaries, player profiles, injury reports) that all link back to the hub. This structure tells the search bots exactly how your content relates. It turns a scattered archive into an organized library. It signals that you are not just reporting news; you are curating knowledge.

The Myth of Keyword Stuffing and the Rise of Natural Language Decades ago, unethical SEOs (Black Hat) would "stuff" keywords into text to trick engines. Today, this is a death sentence. With modern Large Language Models (LLMs) analyzing your text, naturalness is a ranking factor. The AI is looking for semantic richness. It analyzes whether the vocabulary used matches what an expert would naturally use. It looks for synonyms and related concepts (LSI keywords). The best advice for your editors? Write for the reader, not the robot. If a sentence sounds robotic to you, it will look like spam to the AI.

Cannibalization In a print newspaper, you would never run two headlines on page one about the exact same story. Yet, on digital, publishers often commit Keyword Cannibalization. This happens when multiple pages on your site compete for the same topic (e.g., five different short articles about the same town council meeting). This confuses the AI. It doesn't know which version is the authoritative one, so it often ignores them all. The solution is consolidation: update the main story or link the smaller updates to a central "live blog" or pillar page.

IV. The Technical Foundation: Why Speed is Reliability

We often hear publishers say, "My readers don't care about code; they care about the story." This is true, but the machine that delivers the story cares deeply about code.

Core Web Vitals and INP Google measures user experience through Core Web Vitals. The newest and most critical of these for 2026 is INP (Interaction to Next Paint). Simply put, INP measures responsiveness. When a user taps "Menu" or clicks an image gallery, how long before the screen actually changes? If there is a lag—a "stutter"—Google penalizes the site. For local news sites, often burdened with heavy programmatic ads and third-party scripts, INP is a common failure point. A poor INP score tells Google your site is frustrating. In an era where AI answers are instant, a slow website is an relic.

The "100/100" Myth There is a pervasive myth that you must achieve a perfect 100/100 score on Google PageSpeed Insights. This is a vanity metric. Do not burn your budget chasing a perfect laboratory score. Focus on Field Data (data from real users). If your real-world users are having a "Good" experience (green zone), that is sufficient. The goal is pass/fail, not perfection. Your resources are better spent on journalism than on shaving milliseconds off a script load time, provided you are within the "Good" threshold.

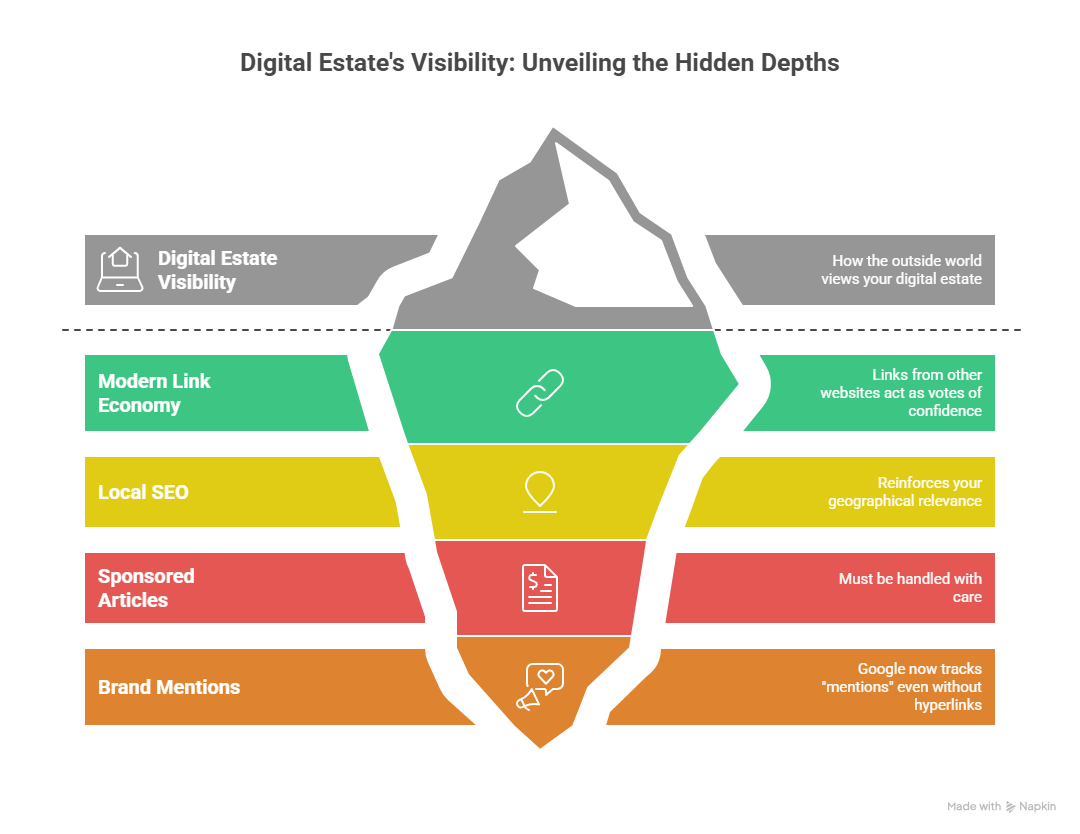

V. Building Reputation: Off-Page Signals

Finally, we must address how the outside world views your digital estate.

The Modern Link Economy Links from other websites act as votes of confidence. However, the logic has changed. Quantity is irrelevant; quality is everything. For a local publisher, a link from a massive, unrelated directory is worthless. But a link from a local Chamber of Commerce, a local high school, or a neighboring county's news site is gold. This is Local SEO. It reinforces your geographical relevance. We also see that links in Sponsored Articles must be handled with care. The days of buying links to boost rank are over; such practices are now easily detected and penalized. Sponsored content is for branding and traffic, not for manipulating Google.

Brand Mentions as "Implied Links" Here is a fascinating evolution: Google now tracks "mentions" even without hyperlinks. If your newspaper is discussed in a forum, cited in a research paper, or mentioned on social media, the AI picks up on this "sentiment." It contributes to your E-E-A-T score. This means your reputation in the community—the actual, offline conversations—now impacts your digital rankings.

Conclusion: The Signal Endures

In 1933, the newspaper owners at the Biltmore Hotel feared that the speed of radio would make the depth of print irrelevant. They were afraid that the "capsule" format of a news bulletin would destroy the appetite for the full story.

They underestimated the American public. The radio bulletin didn't kill the newspaper; it wetted the appetite for it. People heard the headline, but they turned to the paper to understand what it meant.

The situation in 2026 is no different. The AI Overview is the new radio bulletin—fast, summarized, and convenient. But it is surface-level. It cannot hold the government accountable. It cannot capture the emotion of a high school championship game. It cannot investigate corruption.

Your role as a publisher has evolved. You are no longer just printing pages; you are feeding the Knowledge Graph. You are the verifier of reality in an age of synthetic media.

The technical concepts we’ve discussed—AEO, E-E-A-T, INP, Entities—are not obstacles. They are simply the new specifications for your printing press. They are the tools that ensure your signal cuts through the static.

At 4media, we have observed this transition intimately. We see everyday that when legacy publishers upgrade their infrastructure—moving to platforms like CMS4media that handle the technical schema and speed requirements automatically—they stop worrying about the "delivery mechanism" and return to what they do best: journalism.

The medium has changed. The delivery is digital. The summarizer is an AI. But the fundamental value proposition remains exactly what it was when the ink was still wet in 1933:

Trust is the only asset that matters. And you have more of it than any machine ever will.